Mooncake Joins PyTorch Ecosystem

12 Feb 2026, 10:38 pmWe are thrilled to announce that Mooncake has officially joined the PyTorch Ecosystem! By integrating Mooncake’s high-performance KVCache transfer and storage capabilities with PyTorch-native inference engines like SGLang, and vLLM, and TensorRT-LLM, we are unlocking new levels of throughput and scalability for large language model deployments.

To view the PyTorch Ecosystem, see the PyTorch Landscape. Learn more about how projects can join the PyTorch Ecosystem.

About Mooncake

Mooncake is designed to solve the “memory wall” in LLM serving. As context lengths grow and models scale, the static binding of Key-Value (KV) cache to specific GPU workers becomes a primary bottleneck.

Mooncake empowers inference engines to break this binding, unlocking four critical capabilities:

- (Encoder) Prefill-Decode Disaggregation: Mooncake’s high-performance Mooncake Transfer Engine separates heavy computation (prefill/encoder) from latency-sensitive generation (decoding) into distinct clusters.

- Global KVCache Reuse: By acting as a distributed shared memory for KV blocks, Mooncake Store enables valid cache to be reused globally across different requests and engine instances.

- Elastic Expert Parallelism: By decoupling experts from specific workers, Mooncake-EP enables elastic and resilient serving where experts of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models can be dynamically routed or recovered, ensuring high availability even during partial node failures.

- PyTorch Distributed Backend: Mooncake Backend serves as a fault-tolerant PyTorch distributed backend. It provides robust collective communication primitives capable of continuing operation seamlessly in the presence of rank failures.

- Weighs Updating: Mooncake Store enables rapid weight updates for RL and checkpoint scenarios by storing weights internally. It offers tensor-native and zero-copy APIs.

Wide Industry Adoption

Mooncake originated from a research collaboration between Moonshot AI and Tsinghua University. It was born from the need to solve the “memory wall” in serving massive-scale models like Kimi. Since open-sourcing, it has evolved into a thriving community-driven project.

Mooncake’s architecture has been battle-tested in some of the world’s most demanding production environments. Its ability to decouple compute from memory has led to wide adoption across leading organizations, including Moonshot AI (Kimi), Alibaba Cloud, Ant Group, JD.com, Tencent, Meituan, Approaching.AI and LightSeek Foundation.

These organizations utilize Mooncake to maximize GPU utilization and ensure smooth serving for millions of concurrent users.

In Action: A Joint Solution

To demonstrate the full potential of this architecture, we present a joint solution that combines Mooncake with the ecosystem’s leading inference engines and orchestration tools.

In this architecture, we will use RoleBasedGroup (RBG, https://github.com/sgl-project/rbg) to orchestrate the entire topology, defining the relationships and startup order of the cluster. It deploys Shepherd Model Gateway (SMG, https://github.com/lightseekorg/smg) as the critical routing layer, which intelligently directs incoming requests to the appropriate workers based on cache locality and system load. The heavy lifting is then performed by SGLang (https://github.com/sgl-project/sglang) or vLLM (https://github.com/vllm-project/vllm) instances serving as compute workers, while Mooncake functions as the high-speed data plane: its Transfer Engine pushes prefilled KV cache via RDMA/NVLink, and its Store persists that cache for global reuse by decoding nodes.

1. Deployment with SGLang + Mooncake + SMG

Below is the RBG configuration that immediately deploys a complete SGLang architecture. In this case, both Prefill-Decode Disaggregation and Global KVCache-Reuse are enabled. The Prefill instances utilize Mooncake TE to transfer kvcache to Decode instances, while Mooncake Store facilitates reusing KVCache across different requests within the Prefill instance (more details in KEP-74 Mooncake Integration and pd-disaggregated-with-mooncake.yaml).

YAML # Joint Solution: RBG + SMG + SGLang + Mooncake (Production Ready) apiVersion: workloads.x-k8s.io/v1alpha1 kind: RoleBasedGroup metadata: name: sglang-mooncake-smg-v2 spec: roles: # 1. Mooncake Master: Centralized Metadata Server for TE and Store - name: mooncake-master replicas: 1 template: spec: containers: - name: master image: lmsysorg/sglang:latest env: - name: POD_IP valueFrom: fieldRef: fieldPath: status.podIP command: ["mooncake_master"] args: - --enable_http_metadata_server=true - --rpc_address=$(POD_IP) - --rpc_port=50051 - --http_metadata_server_host=$(POD_IP) - --http_metadata_server_port=8080 - --metrics_port=9003 # 2. Mooncake Store: Distributed KVCache Storage Nodes - name: mooncake-store replicas: 3 dependencies: ["mooncake-master"] template: spec: containers: - name: store-node image: lmsysorg/sglang:latest env: - name: MOONCAKE_MASTER value: "s-sglang-mooncake-smg-v2-mooncake-master:50051" - name: MOONCAKE_TE_META_DATA_SERVER value: "http://s-sglang-mooncake-smg-v2-mooncake-master:8080/metadata" - name: MOONCAKE_GLOBAL_SEGMENT_SIZE value: "45gb" - name: MOONCAKE_PROTOCOL value: "rdma" # Use RDMA for zero-copy KVCache transfer command: ["python3", "-m", "mooncake.mooncake_store_service"] resources: limits: memory: "50Gi" rdma/hca: 1 # Required for high-speed TE transfer requests: memory: "50Gi" rdma/hca: 1 # 3. Prefill Worker (SGLang): High-throughput Prefill with Mooncake Push - name: prefill-worker replicas: 1 dependencies: ["mooncake-master", "mooncake-store"] template: spec: containers: - name: sglang-prefill image: lmsysorg/sglang:latest env: - name: MOONCAKE_MASTER value: "s-sglang-mooncake-smg-v2-mooncake-master:50051" - name: MOONCAKE_TE_META_DATA_SERVER value: "http://s-sglang-mooncake-smg-v2-mooncake-master:8080/metadata" - name: MOONCAKE_PROTOCOL value: "rdma" command: - python3 - -m - sglang.launch_server - --model-path /models/Qwen3 - --tp 4 - --disaggregation-mode prefill - --disaggregation-transfer-backend mooncake # Activates Mooncake TE for KVCache Push - --enable-hierarchical-cache # Enables KVCache offloading - --hicache-storage-backend mooncake # Uses Mooncake as the L2/L3 cache backend resources: limits: nvidia.com/gpu: "4" rdma/hca: 1 # 4. Decode Worker (SGLang): Low-latency Generation with Mooncake Pull - name: decode-worker replicas: 2 dependencies: ["mooncake-master", "prefill-worker"] template: spec: containers: - name: sglang-decode image: lmsysorg/sglang:latest command: - python3 - -m - sglang.launch_server - --model-path /models/Qwen3 - --tp 4 - --disaggregation-mode decode # Pulls shared KVCache from Mooncake Store resources: limits: nvidia.com/gpu: "4" rdma/hca: 1 # 5. Shepherd Model Gateway (SMG): Intelligent PD-Disaggregation Router - name: smg-router replicas: 1 dependencies: ["prefill-worker", "decode-worker"] template: spec: containers: - name: router image: lightseekorg/smg:latest command: - smg - --pd-disaggregation - --prefill http://s-sglang-mooncake-smg-v2-prefill-worker:8000 - --decode http://s-sglang-mooncake-smg-v2-decode-worker:8000 - --host 0.0.0.0 - --port 8000

2. Deployment with vLLM + Mooncake

vLLM has also integrated Mooncake support, allowing users to leverage Mooncake connectors for seamless KV transfer. Below is the equivalent rbg() solution for deploying vLLM in a disaggregated setup using Mooncake connectors.

YAML # Joint Solution: RBG + vLLM + Mooncake Connector apiVersion: workloads.x-k8s.io/v1alpha1 kind: RoleBasedGroup metadata: name: vllm-pd-with-mooncake-demo spec: roles: # 1. Gateway: Routing to vLLM instances (SMG or vLLM Proxy) - name: proxy dependencies: [ "prefill", "decode" ] replicas: 1 template: spec: containers: - name: proxy image: lightseekorg/smg:latest command: - smg - --prefiller-host - http://vllm-pd-with-mooncake-demo-prefill-0.s-vllm-pd-with-mooncake-demo-prefill - --prefiller-port - "8000" - --decoder-host - http://vllm-pd-with-mooncake-demo-decode-0.s-vllm-pd-with-mooncake-demo-decode - --decoder-port - "8000" # 2. Prefill Worker (vLLM): Producer role - name: prefill replicas: 1 template: spec: volumes: - name: model persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: qwen2.5-7b - name: dshm emptyDir: medium: Memory sizeLimit: 30Gi containers: - name: prefill image: vllm/vllm-openai:latest command: - sh - -c - | pip install mooncake-transfer-engine && \ vllm serve /models/Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct \ --port 8000 \ --tensor-parallel-size 4 \ --kv-transfer-config '{"kv_connector":"MooncakeConnector","kv_role":"kv_producer"}' ports: - containerPort: 8000 name: http readinessProbe: initialDelaySeconds: 30 periodSeconds: 10 tcpSocket: port: 8000 resources: limits: nvidia.com/gpu: "4" rdma/hca: 1 memory: "100Gi" requests: nvidia.com/gpu: "4" rdma/hca: 1 memory: "100Gi" volumeMounts: - mountPath: /models/Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct name: model - mountPath: /dev/shm name: dshm # 3. Decode Worker (vLLM): Consumer role - name: decode replicas: 1 template: spec: volumes: - name: model persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: qwen2.5-7b - name: dshm emptyDir: medium: Memory sizeLimit: 30Gi containers: - name: decode image: vllm/vllm-openai:latest command: - sh - -c - | pip install mooncake-transfer-engine && \ vllm serve /models/Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct \ --port 8000 \ --tensor-parallel-size 4 \ --kv-transfer-config '{"kv_connector":"MooncakeConnector","kv_role":"kv_consumer"}' ports: - containerPort: 8000 name: http readinessProbe: initialDelaySeconds: 30 periodSeconds: 10 tcpSocket: port: 8000 resources: limits: nvidia.com/gpu: "4" rdma/hca: 1 memory: "100Gi" requests: nvidia.com/gpu: "4" rdma/hca: 1 memory: "100Gi" volumeMounts: - mountPath: /models/Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct name: model - mountPath: /dev/shm name: dshm --- apiVersion: v1 kind: Service metadata: labels: app: vllm-pd-with-mooncake-demo name: vllm-pd-with-mooncake-demo namespace: default spec: ports: - name: http port: 8000 protocol: TCP targetPort: 8000 selector: rolebasedgroup.workloads.x-k8s.io/name: vllm-pd-with-mooncake-demo rolebasedgroup.workloads.x-k8s.io/role: proxy type: ClusterIP

Conclusion

Mooncake adds a vital layer of memory virtualization to the open-source AI stack. By enabling PyTorch engines—whether SGLang, vLLM, or TensorRT-LLM —to adopt KVCache-centric architectures, we are paving the way for more efficient, scalable, and lower-latency LLM services.

We invite you to explore the project and start building:

- Mooncake GitHub: https://github.com/kvcache-ai/Mooncake

Mooncake Project Doc: https://kvcache-ai.github.io/Mooncake/

Pyrefly Now Type Checks PyTorch

12 Feb 2026, 8:30 pmWe’re excited to share that PyTorch now leverages Pyrefly to power type checking across our core repository, along with a number of projects in the PyTorch ecosystem: Helion, TorchTitan and Ignite. For a project the size of PyTorch, leveraging typing and type checking has long been essential for ensuring consistency and preventing common bugs that often go unnoticed in dynamic code. Migrating to Pyrefly brings a much needed upgrade to these development workflows, with lightning-fast, standards-compliant type checking and a modern IDE experience. With Pyrefly, our maintainers and contributors can catch bugs earlier, benefit from consistent results between local and CI runs, and take advantage of advanced typing features. In this blog post, we’ll share why we made this transition and highlight the improvements PyTorch has already experienced since adopting Pyrefly.

Why Switch to Pyrefly?

To support the future development of PyTorch, we wanted a type checker that is fast, easy to use, consistent across developer environments, and actively maintained. These factors ultimately influenced the decision to move forward with Pyrefly.

Balancing Speed with Accuracy

In a recent round of benchmarking type checking Pytorch took 50.6 seconds using MyPy, whereas Pyrefly (v44.1) took only 5.5 seconds. This is a significant speed improvement over Pytorch’s existing tooling while still maintaining robust type safety. We wanted an alternative that not only delivered fast results, but would also help our contributors catch bugs early and identify gaps in our type coverage. Pyrefly appears to strike the right balance for us, being fast enough to keep up with our development speed without compromising on the quality of type safety.

That said, we see this as just the beginning; there is still room for Pyrefly to become even faster, and we expect to benefit from even greater speed gains as the tool continues to evolve. We’ll be closely following Pyrefly’s ongoing development and look forward to integrating future performance enhancements as they become available.

Simplified Configuration

Previously, our reliance on MyPy required contributors to juggle multiple configuration files to manage coverage and strictness levels across the codebase. This made it difficult to determine exactly which files were being checked and under what specific rules. Transitioning to Pyrefly has helped address these challenges. With direct support from the Pyrefly team, PyTorch has now transitioned to use a single unified Pyrefly configuration and required suppressions, making it much easier for our maintainers to understand which files are being typechecked and how.

Consistency across Development Environments

Previously, developers often encountered discrepancies between their IDE, local CLI, and the CI environment because different type-checking engines were being used at each stage. MyPy might be used in PyTorch CI jobs, but when it comes to IDEs, other type checkers were preferred that behaved slightly differently. Or developers would have a different MyPy strictness mode enabled for their CLI runs that differed from what was used in CI. These inconsistencies led to unpredictable feedback loops and a frustrating experience where code that passed their local type checking run would fail in CI. By adopting Pyrefly, which provides a high-quality IDE experience alongside robust CLI and CI functionality, PyTorch developers can now benefit from consistent results across all their development environments.

| Before | After | |

| CI | MyPy (full project run) | Pyrefly |

| CLI | MyPy (only on select files) | Pyrefly |

| IDE | Pyright OR other | Pyrefly |

Active Maintenance and Rapid Development

Another major reason for migrating is that Pyrefly is actively maintained and evolving quickly, with significant room for continual performance improvements. We’ve appreciated the responsiveness to user feedback and the rapid development cycles, which include new minor releases every Monday. It’s not uncommon for a bug to be reported and resolved in time for the very next release, ensuring that issues are addressed and new features are delivered promptly. An example of this is described in a recent Pyrefly blog post, where a performance bottleneck was identified and promptly resolved, resulting in an 18x speed up in IDE responsiveness across the PyTorch codebase.

Throughout this migration, and as we continue using Pyrefly, our priority is to avoid regressions in type safety or developer experience. Maintaining a regular line of communication with the Pyrefly team has been essential for quickly addressing edge cases and enabling a smooth transition for our contributors.

Additional Benefits for PyTorch Contributors

PyTorch contributors and maintainers have already experienced meaningful improvements since moving to Pyrefly. Beyond the initial motivations for the transition, other benefits include the following:

Improved code quality

The rollout of Pyrefly has already led to the discovery and resolution of numerous bugs in the PyTorch codebase. One factor that helped achieve this was due to the fact that Pyrefly runs in a consistent mode across Pytorch. Take the code example below: unless MyPy is in strict mode, it doesn’t type check the bodies of untyped functions, meaning errors like this would possibly go unnoticed. Pyrefly, on the other hand, runs in one consistent mode across the codebase and is able to catch these types of errors.

def foo():

return 1 + "" # pyrefly errorSeamless IDE Experience

Pyrefly integrates natively with many major IDEs, bringing real-time type feedback, hover documentation, and instant diagnostics directly into the editor that match your local and CI results. Now PyTorch contributors using a diverse range of IDEs can spot type errors as they code and be confident their results are consistent, reducing context-switching and making it easier to maintain high code quality. VSCode users can download our IDE extension here. Once enabled, it will automatically find the configuration file in the PyTorch project.

Advanced Typing Capabilities

Pyrefly brings advanced typing features to PyTorch, including robust support for complex typing patterns and strict adherence to Python typing specifications. This empowers contributors to write safer and more expressive code, while maintaining performance and a smooth developer experience.

Pyrefly’s inference capabilities can also enable developers to detect type errors even in code that lacks explicit type annotations. This means that legacy code, experimental modules, and fast-moving prototypes can benefit from increased type safety, without requiring a massive upfront investment in annotation. It can also help identify areas of code that could benefit from more explicit type annotations, helping us move forward with our goals of increasing type coverage in the codebase. Currently, return type inference is not enabled by default in PyTorch, but we are actively working to add annotations and fix type issues in order to un-gate this feature in the near future.

def foo():

return 1

foo() + "hello" # mypy: no error, # pyrefly: error [unsupported-operation]Get Started with Pyrefly

Contributors to PyTorch can get started using Pyrefly by installing the extension in their editors, and can start using it for local type checking quickly and easily using lintrunner:

lintrunner init

lintrunnerContributors to Helion can also get started by installing the IDE extension and can do a local type check by running the repository’s lint.sh file

./lint.sh install && ./lint.shPyrefly is also integrated into our CI suite under the lint job to ensure consistency across the codebase. This ensures that the same rules applied during local development are enforced on every PR. When you open a pull request, you can find the Pyrefly results by navigating to the “Checks” tab and selecting the lint job.

If you’re not a PyTorch contributor but still want to check out Pyrefly on your own project, you can get the VSCode extension here or check out the Pyrefly documentation.

Future Work

Switching to Pyrefly marks a practical and meaningful advancement for the PyTorch project. Developers are already seeing the benefits of faster and more consistent type checking, and the initial rollout has helped uncover and resolve a substantial number of bugs. This transition has streamlined workflows and laid the foundation for ongoing improvements in both code quality and developer experience.

Looking ahead, we hope to continue seeing performance improvements from Pyrefly as the tool matures. We’re also excited to partner with the Pyrefly team to further improve typing across the codebase. Strengthening type annotations in one of the most widely used AI/ML libraries will enable maintainers and the broader community to more confidently leverage PyTorch in production environments. Deploying a newer, faster type checker with Pyrefly is only the first step of that journey.

As always, community feedback is invaluable. We encourage PyTorch contributors and users to share their experiences, report issues, and suggest improvements as we continue refining the type checking workflow. If you have questions or wish to provide feedback to the Pyrefly team, you can do so in Discord, or submit bug reports by opening a GitHub issue in the Pyrefly repository.

Finally, we want to extend our sincere thanks to both the PyTorch and Pyrefly teams, as well as the community, for their feedback and testing throughout this transition.

Why I’m Joining the PyTorch Foundation

11 Feb 2026, 4:55 pm

I want to start by thanking Matt White for everything he has built over the past two years. The growth of the PyTorch Foundation speaks for itself. What began as a single-project foundation is now a multi-project home for some of the most critical infrastructure in AI. That did not happen by accident. It is the result of real technical leadership, genuine community investment, and a clear belief in open collaboration. Matt is now stepping into the role of Global CTO of AI at the Linux Foundation and will transition to the role of CTO at the PyTorch Foundation, where he will focus on the technical strategy and direction that will define what’s possible next.

I’m thrilled to be joining the PyTorch Foundation as its new Executive Director. Here’s why.

The Most Important Open Source Projects in the World

There is not a more important open source project in the world right now than PyTorch. The daily onslaught of new state-of-the-art models proves it. When you hear about models writing compilers from scratch capable of compiling the Linux kernel, you’re getting a glimpse of the future that PyTorch makes possible.

But here’s what I think people outside of our community are only beginning to understand: the PyTorch Foundation is no longer just about PyTorch.

vLLM has become the inference engine of choice for the industry. When a new model drops, it runs on vLLM on day one, which tells us where the center of gravity lives. Inference is the largest workload in human history, and it runs on a PyTorch Foundation project.

DeepSpeed is pushing the boundaries of training efficiency at a scale that was unthinkable a few years ago. Ray is powering the orchestration and scaling layer that lets AI workloads run across the industry. These are foundational technologies with massive communities of their own, and they chose to make their home here.

Training. Inference. Orchestration. The critical layers of the AI stack live under one roof.

Every Innovation Story Is an Infrastructure Story

I’ve spent my career finding the infrastructure layer of emerging technology waves and building open source ecosystems around them. I co-founded OpenStack in 2010 and built the OpenStack Foundation (now OpenInfra Foundation), spending over a decade helping create the open source cloud. Last year we merged the OpenInfra Foundation with the Linux Foundation, and I became General Manager of AI and Infrastructure and Executive Director of the LF AI and Data Foundation. Now I get to put that experience into action with the PyTorch Foundation.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned across all of that, it’s that every innovation story is an infrastructure story if you know where to look. AI is going to reshape every aspect of the lives of every human being on earth, and it is going to do so at a speed that makes previous technological transitions look slow. The industrial revolution played out over generations. The internet transformed society over decades. AI is compressing that arc into years. The infrastructure that makes all of this possible is being built right now, in the open, by the communities in this foundation

We don’t want any one company or country to dominate such critical technologies. They have to be built together by communities that trust each other enough to do the hard work side by side. The best open source foundations foster the conditions that let communities lead. They keep the path open for the widest possible participation and the largest possible impact. That’s what we need to do again, and I’m here to do that work with all of you.

The Energy Is Real

I had the opportunity to attend PyTorchCon in San Francisco last October, and I was in awe of the community energy in that place. That’s not easy to pull off in Moscone, and it’s not something you’ll find at just any open source conference. I’ve been to many of them. It reminded me deeply of the early OpenStack days when our summits were doubling every year, and people were genuinely having fun while changing the world.

If you’re part of this community, whether you contribute to PyTorch, vLLM, DeepSpeed, Ray, or the ecosystem around them, you may not fully realize it yet, but that’s exactly what you’re doing. Enjoy the ride.

What Comes Next

My prime directive is clear. Serve the communities that make this foundation what it is. Advocate for the open path that leads to the most innovation, the widest impact, and the largest number of people served by this technology. And make sure that every community that calls this foundation home knows that it belongs here and that its work matters.

If you’re headed to a PyTorch Conference, a PyTorch Day, or anywhere else this community gathers, come find me. I want to meet the people doing this amazing work. The best part of open source has always been the people, and I can’t wait to get to know more of you.

Let’s go build the future.

Mark Collier is Executive Director of the PyTorch Foundation, General Manager of AI and Infrastructure at the Linux Foundation, and Executive Director of the LF AI and Data Foundation. He co-founded the OpenStack project in 2010 and spent 13 years building the OpenStack Foundation and open source cloud community.

PyTorch Foundation: The Next Chapter, Together

11 Feb 2026, 4:55 pm

Over the past nearly two years, I’ve had the privilege of serving as Executive Director of the PyTorch Foundation. As I look back on what we have accomplished together, one thing stands out clearly: our momentum is not accidental. It is the result of a global community of maintainers, contributors, researchers, practitioners, member organizations, and volunteers who have chosen collaboration, openness, and technical rigor as the path to progress.

This post is both a thank you and a transition update, shared first and foremost with the PyTorch community.

What we built in a short time

In a relatively short period, the PyTorch Foundation has evolved from a single-project foundation centered on PyTorch into a multi-project home for critical components across the AI development lifecycle. Today, the Foundation proudly hosts four major projects: PyTorch, vLLM, DeepSpeed, and most recently Ray. Alongside these hosted projects, the broader PyTorch ecosystem has expanded to more than 100 projects, including Unsloth, verl, SGLang, FEAST, and many other high-quality open source efforts that are pushing the state of the art forward.

At the same time, our membership has grown to 33 organizations, nearly doubling, and we updated our membership tiers to better reflect the scale and maturity of our ecosystem. Those member commitments matter, because they translate into real investment in the shared infrastructure and community programs that enable open source AI to thrive.

Stronger governance and deeper technical collaboration

As our technical scope expanded, so did our governance. We launched the initial Technical Advisory Council and supported its growth into a more active forum for cross-project alignment. We also established five core working groups: CI Infrastructure, Multi-Cloud, Ecosystem, Accelerators, and Security.

These groups are where hard, practical problems get solved: keeping CI reliable and scalable, improving portability and cost efficiency, coordinating cross-project priorities, strengthening security posture, and making it easier for developers and organizations to adopt and deploy PyTorch and related projects. The result has been measurably increased technical engagement, clearer project roadmaps, and more consistent collaboration patterns across the Foundation’s hosted projects and the broader ecosystem.

A bigger global footprint, powered by the community

The growth of PyTorch is global, and our community programs have expanded accordingly.

We grew from a conference of roughly 300 attendees to a flagship PyTorch Conference in San Francisco that welcomed more than 3,000 participants. We successfully launched PyTorch Days with events in Paris and Beijing, and we are continuing to expand our global presence. In 2026, we will hold three PyTorch Conferences: Europe in Paris (April), China in Shanghai (September), and our flagship event, North America in San Jose (October). These will be complemented by additional PyTorch Days, starting in Bengaluru this past weekend, with more events in development, including Beijing, Seoul, and others.

We also launched the PyTorch Ambassadors program, now approaching 50 ambassadors, with another cohort planned. This is one of the most important community programs we run, because it scales something no single team can manufacture: local leadership. Ambassadors host meetups, welcome new contributors, and help PyTorch show up meaningfully in regions and communities around the world. In parallel, we’ve been building a speaker bureau to connect domain experts from the community with events seeking credible technical speakers.

Academic outreach, research engagement, and education

Another area of focus has been strengthening ties between research, education, and open source practice.

We kicked off an Academic and OSPO outreach program to engage academic labs and university Open Source Program Offices, with early work involving UC Berkeley, UC Santa Cruz, Stanford, the University of Vermont, and Caltech. The goal is to help students build practical open source skills, create clearer pathways from research to production, and identify emerging open source AI projects that could benefit from Foundation support.

We also increased the Foundation’s participation in major research and practitioner venues, supporting workshops, posters, and talks at MLSys, ICML, NeurIPS, and UC Berkeley’s AgentX program. Across the year, I joined many leaders from the PyTorch community in speaking at more than 100 events worldwide to advocate for PyTorch, the Foundation, and open source AI as a durable strategy for innovation.

Finally, the educational output from the community has been exceptional. In 2025, we published more than 130 pieces of educational content, including tutorials, webinars, and blogs, averaging nearly one substantive item every three days. That pace reflects both the depth of expertise across the community and the rate at which the ecosystem continues to evolve.

We also made meaningful progress toward scalable professional development. At the last PyTorch Conference, we kicked off onsite training for the PyTorch Certified Associate program with strong participation. In the coming months, we expect to publish the corresponding exam and online course, and then begin building the content pathway toward a PyTorch Certified Professional designation. The intent is to support developers who want to demonstrate practical PyTorch fluency, while giving employers a clearer signal for hiring and workforce development.

Infrastructure that scales with the ecosystem

Behind every reliable open source ecosystem is infrastructure that works. Over the past two years, we continued strengthening CI reliability and observability, expanded monitoring and logging, and progressed the migration of our download site to the Cloudflare CDN.

Just as importantly, the Foundation’s CI would not be sustainable without the support of member organizations and partners who contribute engineering effort, hardware, and operational expertise. Contributions, current and in progress, from Meta, AWS, AMD, Intel, Microsoft, and NVIDIA have been critical. We have also advanced a multi-cloud strategy so we can diversify our footprint across hyperscalers and neo-clouds, manage cost, and maintain the performance and scale that developers and production users depend on.

What comes next

Even with this progress, the next phase demands more. Key priorities ahead include:

- Expanding the hosted project portfolio, including adjacent domains such as agentic AI, environments, and reinforcement learning

- Further diversifying and optimizing CI architecture and costs

- Onboarding additional project CI workloads where shared accelerator access unlocks faster iteration

- Expanding training and certification into a durable revenue stream that strengthens Foundation sustainability

- Deepening community programs, including initiatives such as mentorship and stronger global enablement

As the scope grows, there is a straightforward operational reality: leadership capacity must scale so that organizational throughput, not leadership bandwidth, sets our pace.

A leadership transition to support the next stage

To support this next stage, I’m sharing a leadership transition that takes effect immediately.

I will be stepping into the role of Chief Technology Officer for the PyTorch Foundation, alongside my new role as Global CTO of AI at the Linux Foundation. At the same time, Mark Collier will join the PyTorch Foundation as our new Executive Director.

Mark brings deep experience building and scaling open infrastructure ecosystems, including founding OpenStack and the OpenInfra Foundation. As Executive Director, he will lead the operational and business execution of the Foundation, working closely with the Governing Board. His responsibilities include oversight of Foundation committees (including Finance and Marketing), community programs such as Ambassadors, Foundation-led events, staff management, finances, and membership development. Ultimately, he will be accountable for the overall direction and operations of the Foundation in partnership with the Governing Board.

As CTO, I will focus on technical strategy and execution across the Foundation: supporting the TAC and working groups; advancing our hosted projects and ecosystem alignment; strengthening CI and multi-cloud infrastructure; and driving technical programs, including Academic and OSPO outreach and PyTorch Certified. This structure is intended to increase clarity, accountability, and speed, while preserving community-led technical governance.

Quotes

“It’s great to see the PyTorch Foundation enter a new phase, just months after it evolved into an umbrella foundation. With Mark as the Executive Director and Matt as the CTO, the foundation acquires the level of maturity required by its ambitions. I can’t wait to help build the future of PyTorch with the new leadership and the rest of the TAC.”

– Luca Antiga, CTO, Lightning AI and Chair, PyTorch Foundation Technical Advisory Council (TAC)

“Watching the PyTorch Foundation grow into an umbrella ecosystem has been inspiring—it’s set PyTorch up not only for the short term, but for a long arc of impact foundational to AI. Congrats to Matt on an incredible chapter, and a warm welcome to Mark. I’m excited for where we take PyTorch next!”

– Joe Spisak, Product Director, Meta Superintelligence Labs & PyTorch Core Maintainer

“The growth of the PyTorch Foundation speaks for itself. Thanks to Matt White for everything he has built. What began as a single-project foundation is now a multi-project home for some of the most critical infrastructure in AI. That did not happen by accident. It is the result of real technical leadership, genuine community investment, and a clear belief in open collaboration. I’m excited to keep that momentum going that will define what’s possible next.”

– Mark Collier, Executive Director, PyTorch Foundation

Thank you

I want to close with an explicit note of appreciation. The PyTorch Foundation’s progress is not the product of any single organization or individual. It is the result of thousands of community members: maintainers, contributors, reviewers, working group participants, event organizers, speakers, educators, and member company teams who consistently choose collaboration over fragmentation and long-term stewardship over short-term advantage.

Thank you for the trust, the effort, and the standards you bring to this community.

I’m excited for what comes next, and I’m particularly looking forward to working with Mark as he steps into the Executive Director role. Please join me in welcoming him and supporting him as he begins this next chapter with us.

We have built something strong. Now we scale it.

Matt White

CTO, PyTorch Foundation

Global CTO of AI, Linux Foundation

PyTorch Day India 2026: A builder-focused milestone for open source AI in Bengaluru

10 Feb 2026, 10:35 pmPyTorch Day India 2026: A builder-focused milestone for open source AI in Bengaluru

On February 7, 2026, the inaugural PyTorch Day India brought the open source AI community to Bengaluru for a full day of technical talks, discussions, and community connection. Co-organized by IBM, NVIDIA, and Red Hat, the event reinforced a clear theme: India is not only adopting AI at scale, it is helping define how production-grade, open AI systems are built.

The in-person event was held in Bengaluru, placing the event at the center of one of India’s most active engineering ecosystems with 460 in-person attendees. The event was emceed by Raghu Ganti, IBM, who guided the day’s flow and helped keep the program cohesive and engaging.

Keynotes that framed the day: open platforms shaping the future of open source AI

A strong keynote trio anchored the event, reflecting the co-organizers’ complementary strengths across enterprise platforms, infrastructure software, and accelerated computing.

- Steve Watt (Red Hat): “Any Model, Any Accelerator, Any Cloud: How Open Source AI Unlocks the World’s Potential”

- Sriram Raghavan (IBM): “The Ubiquitous AI Platform: Lessons from Linux, Vision for PyTorch”

- Niket Agarwal (NVIDIA): “Full Stack AI Innovation: PyTorch + NVIDIA From Edge to Data Center”

Taken together, these talks pointed to the operational reality of modern AI, and how platforms like PyTorch and vLLM are laying the foundation for fast innovation from research to production

First, heterogeneous compute has become the default. Teams increasingly mix CPUs, GPUs, and specialized accelerators across cloud and on-premises environments, and they need frameworks and tooling that work consistently across those targets.

Second, AI platforms are increasingly treated as foundational infrastructure. The Linux comparison is instructive because long-lived platforms succeed when they provide stable interfaces, clear governance, and predictable behavior. That stability enables fast iteration above the platform and efficient optimization below it.

Third, end-to-end performance is now a primary product requirement, not an optional enhancement. “Edge to data center” captures the range of deployment patterns that organizations must support, from constrained inference at the edge to large-scale training, fine-tuning, and high-throughput serving in the data center.

What builders came for: kernels, compilers, inference, and real systems work

PyTorch Day India was deliberately technical and builder-oriented. The event emphasized low-level kernel to systems performance work, optimization, training efficiency, inference, and deployment concerns. This reflects where the field is heading: the hardest problems are about making robust and dependable AI systems under real constraints like latency, cost, reliability, security, and governance.

That builder emphasis also showed up in the ecosystem representation and talk topics. For example, Aritra Roy Gosthipaty and Sayak Paul (Hugging Face) highlighted kernel-level work in the Transformers ecosystem, signaling that practical performance engineering is now a first-class conversation for mainstream ML teams.

This focus matches how organizations deploy AI today. Most production AI is not a single model running in isolation. It is a workflow that connects data pipelines, distributed execution, training and evaluation, inference and serving, monitoring, and governance. As these components become more interdependent, open and composable building blocks become essential.

A keynote message worth carrying forward: open source is how AI becomes dependable

In his address, Matt White, PyTorch Foundation CTO and former Executive Director, emphasized a shift that is now common across enterprises. AI is moving from prototype to operational capability. That transition forces teams to prioritize engineering fundamentals, including reproducible training and evaluation, scalable inference, distributed compute and data pipelines, and security and supply-chain hygiene.

He also underscored a broader architectural trend: AI systems are becoming “systems of systems,” where models connect to retrieval, tooling, deployment, monitoring, and governance. In that environment, open source becomes a practical necessity because production adoption benefits from transparency, inspectability, and integration flexibility across complex infrastructure.

Why India matters to the PyTorch Foundation and the global ecosystem

India’s importance to the PyTorch ecosystem is structural.

It has developer scale, talent density, and a strong builder culture that translates research into production systems. It also has broad industry diversity, spanning global capability centers, fast-growing startups, academic institutions, and large enterprises serving both local and international markets. That mix accelerates feedback on what matters most in real deployments.

India also has a mature relationship with open source collaboration. That matters because open ecosystems thrive when communities do more than consume software. They improve it, document it, test it, build extensions, and create learning pathways that expand participation. Events like PyTorch Day India strengthen those pathways by turning knowledge-sharing into sustained contribution.

What comes next: build locally, contribute globally

The most practical takeaway from the inaugural PyTorch Day India is that open source AI maturity is being shaped in many places at once, and India is clearly one of those places. Bengaluru was an appropriate setting, with its dense overlap of research, infrastructure engineering, product development, and startup execution.

For attendees, the next step is straightforward and high leverage: turn one idea from the day into an artifact that others can use. That might be a reproducible benchmark, a tutorial, a bug fix, a performance investigation, a documentation improvement, or a small but meaningful contribution to a project you rely on.

PyTorch Day India 2026 kept the focus where it belongs: on builders, on systems, and on the open technologies that make AI usable across industries and across the world. We hope to launch more PyTorch Day events in India and work together to build a strong, talent-rich, diverse, and cohesive open source AI ecosystem with the community in India.

Accelerating Mamba2 with Kernel Fusion

6 Feb 2026, 10:48 pmSummary

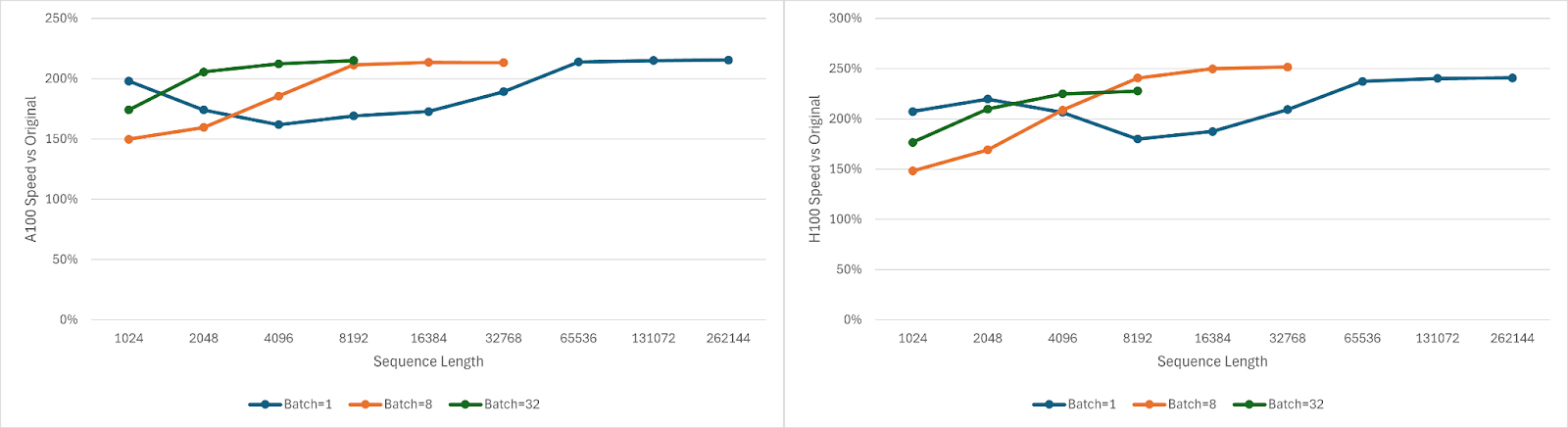

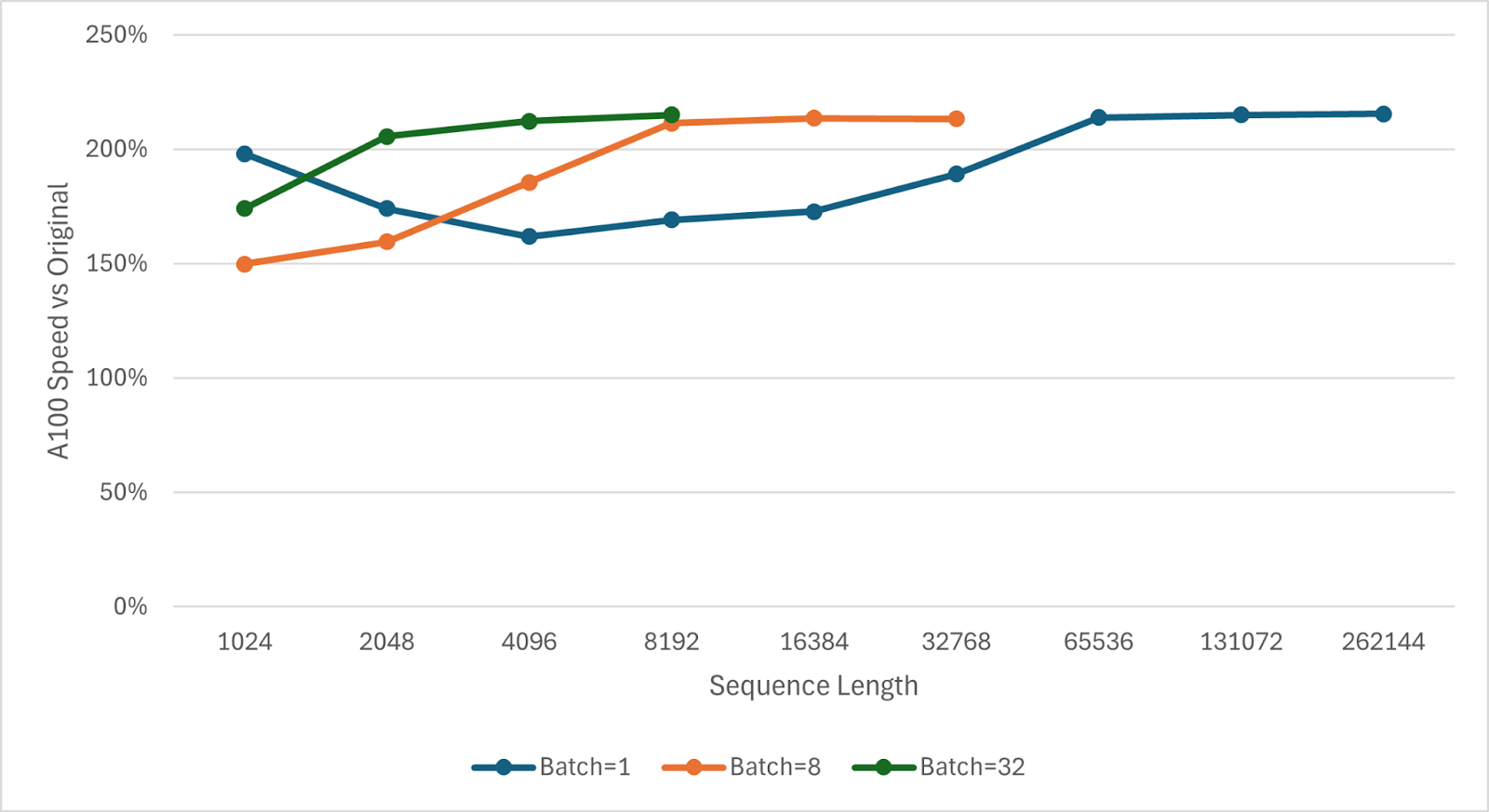

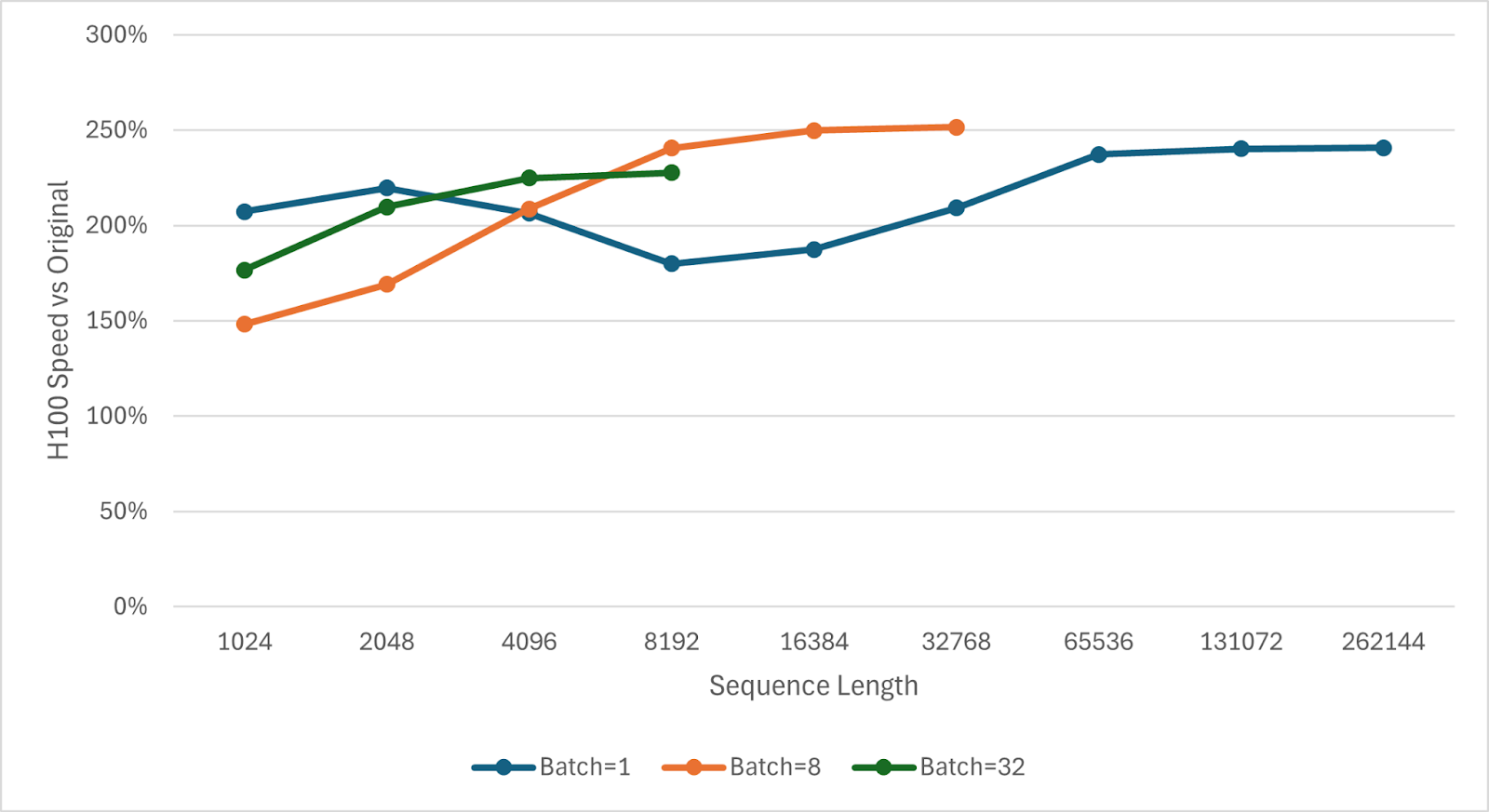

In this post, we discuss how we optimized the Mamba-2 State-Space Dual (SSD) module with a fused Triton kernel that yields speedups of 1.50x-2.51x on NVIDIA A100 and H100 GPUs. To achieve this, we fused all five SSD kernels into a single Triton kernel with careful synchronization. To our knowledge, this is the first end-to-end Triton fusion of all five SSD kernels. This reduces launch overhead and avoids redundant memory operations, making the kernel faster across all input sizes. The rest of this blog will cover how we fused the SSD kernels, what bottlenecks remain, benchmark results, and our plans to release the kernel in the open source so the community can benefit.

Figure 1. Fused SSD Triton Kernel A100 and H100 Speedups

Background

Mamba-2 is a sequence model based on the state-space duality (SSD) framework, which connects structured state-space models (SSMs) with attention-based transformers as an optimized successor to the original Mamba model. One key advantage of Mamba-style models is scalability to long sequences. Mamba’s state-space mechanism scales linearly with context length. In practice, doubling the input sequence length roughly doubles Mamba’s compute and memory needs, whereas self-attention would quadruple them. This makes Mamba-2 especially attractive for extremely long contexts, such as 128K tokens and beyond.

IBM’s Granite 4.0 model family recently adopted a hybrid architecture that combines Mamba-2 blocks with transformer blocks. In Granite 4.0, nine Mamba-2 layers are used for every one attention layer to handle long-range context efficiently. With Mamba-2 becoming integral to such models, optimizing Mamba-2’s performance is critical for faster inference. The core of Mamba-2’s computation is the SSD module, which replaces the attention mechanism in each layer. The original Mamba2 SSD implementation is mostly bottlenecked by memory bandwidth and latency and includes writing and reading intermediate data, so there are opportunities for improvement. In this blog, we focus on accelerating this SSD prefill operation with an optimized fused kernel.

Mamba2 Operations

The operations that make up a typical Mamba2 block are listed in Table 1. We focused on fusing the five SSD kernels because they behave as one conceptual SSD operation, though further fusion (e.g., convolution and layernorm) may be possible as discussed later.

| Layernorm | Helps with numerical stability |

| In Projection | Projects input to SSD channels/size |

| Depthwise Convolution | Mixes the last few tokens |

| SSD Chunk Cumsum | Computes the dt per token and cumulative decay within a chunk |

| SSD Chunk State | Computes the state at the end of this chunk in isolation |

| SSD State Passing | Computes the global states at the end of each chunk |

| SSD BMM | Computes how the each chunk of input x affects the corresponding chunk of output y |

| SSD Chunk Scan | Computes each chunk of y from the corresponding chunk of x and previous chunk’s global state |

| Layernorm | Helps with numerical stability |

| Out Projection | Projects output to the model’s hidden dim |

Table 1. Mamba2 operations

Why Do We Need Kernel Fusion?

During prefill, which is the forward pass over the prompt or input sequence before token generation, Mamba-2’s SSD module executes as a pipeline of five GPU kernels. In the original implementation, these five kernels run sequentially on the GPU.

However, launching multiple small kernels in sequence incurs significant overhead and prevents the GPU from reusing data between stages efficiently. By applying kernel fusion we can get several key benefits:

- Eliminating Kernel Launch Overheads: One launch instead of five reduces CPU-GPU synchronization and scheduling delays.

- Improving Cache Locality: Data produced in one stage is immediately consumed by the next within the same threadblock, increasing cache hits and reducing global memory traffic.

- Overlapping Computation: Different parts of the fused kernel can execute in parallel (where independent), better utilizing GPU resources.

Our solution fuses all five kernels into a single Triton kernel, so that the entire SSD prefill computation for a layer happens within one GPU launch.

Efficient Kernel Fusion Technique

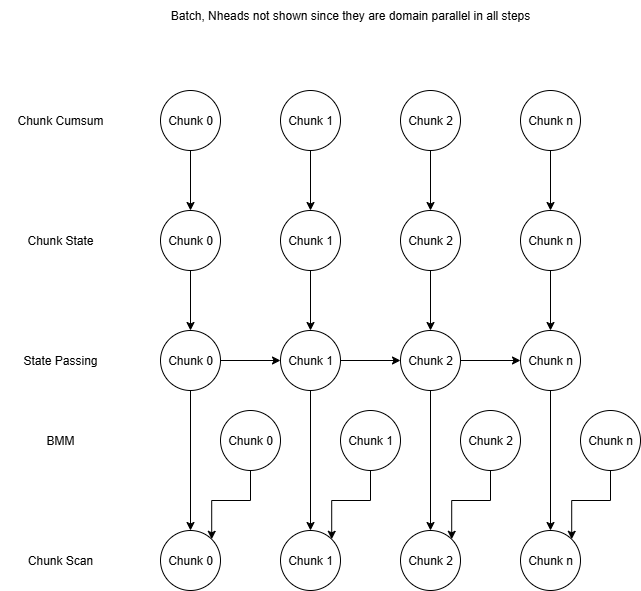

Unlike a simple matmul + activation fusion, SSD fusion is complex because the computation spans multiple steps with complicated dependencies. The original implementation relied on implicit synchronization across kernels, which disappears when we fuse everything. In this section, we discuss why that matters and our approach to making fusion work in practice.

The five steps of the Mamba2 SSD were originally implemented as five separate kernels: Chunk Cumsum, BMM, Chunk State, State Passing, and Chunk Scan, which operate on fixed-size chunks of tokens. The figure below illustrates the dependencies between these kernels.

Figure 2. Mamba2 SSD Prefill Kernel Graph

The State Passing step has dependencies between chunks, and the original State Passing kernel handled this by looping over chunks within threadblocks and splitting the state’s channels across threadblocks for parallelism. With this State Passing loop and the implicit global synchronization between kernel launches, all dependencies were handled in the original kernels.

The real technical challenge comes when we try to fuse all five kernels into a single launch. Once fused, we lose the implicit global synchronization that the original kernels relied on, so we must explicitly manage both within-chunk and across-chunk dependencies. Most of the dependencies are between different steps but the same chunk, so for the three largest kernels, Chunk State, State Passing, and Chunk Scan, these intra-chunk dependencies could be handled by running all steps of a particular chunk on the same threadblock. This would also give us the ability to keep intermediate data between steps in registers or L1 cache (private to each SM) since the data will be used on the same threadblock.

However, this approach is neither possible nor correct. The original State Passing kernel has the aforementioned loop, which makes its threadblock grid not match the original Chunk State and Chunk Scan kernels. Furthermore, having separate threadblocks for each chunk would remove the natural synchronization and correctness provided by looping over chunks within a single threadblock.

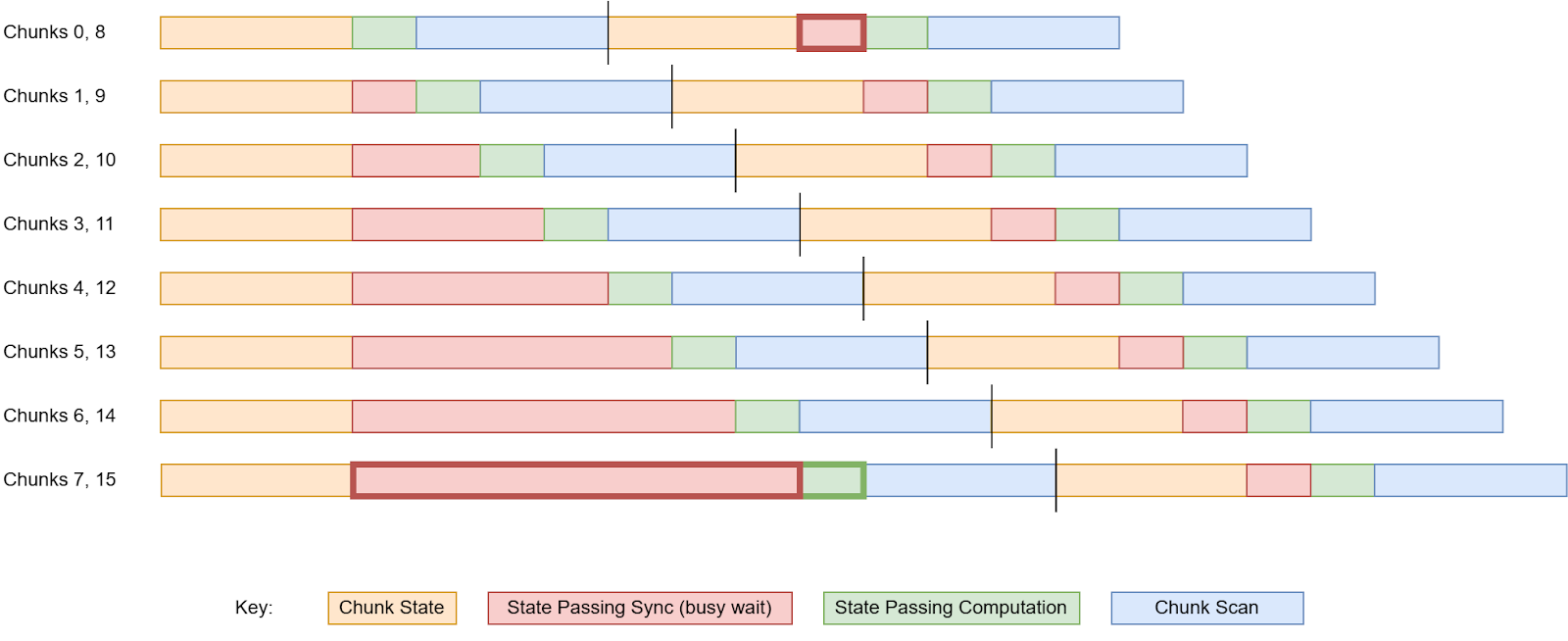

To make fusion possible, we split the iterations of the State Passing loop across chunks into separate threadblocks so the threadblock grids match. We get correctness by ordering these threadblocks with atomics, a form of serialization that looks quite inefficient on the surface but can be mitigated by overlapping with the other two parts.

For example, if we ran 8 chunks in parallel, we would expect a ~8x local slowdown from the State Passing serialization. However, the fused State Passing is a small fraction of the three large steps, especially since it no longer has to read the state from global memory (it’s already in the threadblock from the fused Chunk State).

By Amdahl’s law, we would expect the runtime to change to (State Passing fraction) * 8 + (1 – State Passing fraction) * 1. For example, if the State Passing step was only 1/7th of the combined time excluding synchronization, we would get (1/7) * 8 + (6/7) * 1 = 2, implying a 2x overall slowdown. However, this does not account for overlap. Since the synchronization of State Passing can overlap with the Chunk State and Chunk Scan computation, the slowdown would be roughly:

State Passing compute time + max(other compute time, State Passing synchronization time)

= 1/7 + max(6/7, 1/7 * 7) = 1.14x

If State Passing was a smaller fraction of the total runtime or if less chunks are processed concurrently, we could theoretically avoid any serialization slowdown in all but the first chunks.

Figure 3. State Passing Overhead Overlap

Figure 3 shows the theoretical synchronization delays, which are high for the first chunks run in parallel, but settle down to a low overhead in all later chunks. We can see that although chunk 8 depends on chunk 7, it only has to busy-wait 1 unit of time instead of 8 since the chunk 0 Chunk Scan and chunk 8 Chunk State overlap with the State Passing of chunks 1-6. In practice, NVIDIA Nsight Compute benchmarks show that fewer than 3% of warp stalls (idle thread time) are caused by the State Passing synchronization, implying that the serialization latency is hidden.

The BMM and Chunk Cumsum steps are extremely fast compared to the other three. BMM splits work along ngroups instead of nheads, and Chunk Cumsum has its threadblocks handle multiple heads for efficiency. For simplicity, we launch separate threadblocks for these two steps (the first few threadblocks work on them) and have the threadblocks for the other three steps await their BMM and Chunk Cumsum dependencies with atomics.

When a threadblock begins executing the kernel, it is assigned to work on the Chunk Cumsum step unless all Chunk Cumsum work has already been assigned. Similarly, if there is no unassigned Chunk Cumsum work, the threadblock would be assigned to the BMM step if available. After both of these fast steps have been fully assigned to threadblocks, later threadblocks each start processing a chunk in Chunk State, process that same chunk in State Passing, and finally output that chunk after Chunk Scan.

While kernel fusion improves data reuse and speeds up the SSD, additional optimizations are necessary to achieve maximum performance. These include reordering threadblocks to hide serialization latency, adding cache hints to loads/stores to prioritize reused data, separating special cases outside of the fused kernel to reduce register pressure, changing some intermediate datatypes, tuning the chunk size, and restructuring operations for less latency. These optimization techniques are described in more detail in Appendix A.

Remaining Bottlenecks

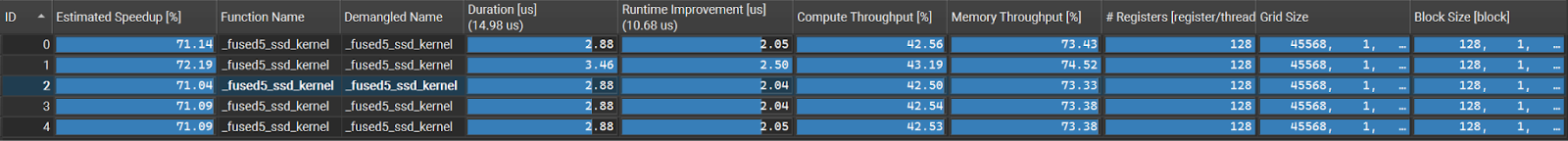

In this section, we analyze the bottlenecks in the optimized fused SSD kernel using Nsight Compute to examine the final utilization, stall patterns, and resource tradeoffs.

At a high level, we can look at the compute and memory utilization of the fused kernel to get an idea of what limits this kernel.

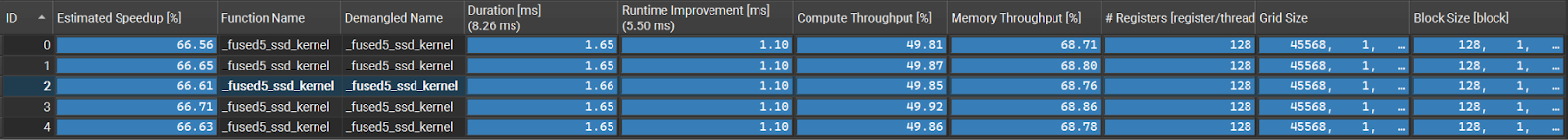

Figure 4. A100 Nsight Compute Summary

Figure 5. H100 Nsight Compute Summary

We can see that overall fused SSD compute utilization is about 40-50% and memory utilization is about 65-75%. It is not possible to achieve 100% utilization due to the initial load/store latency and other overheads, but it’s usually possible to get at least 80% in a well-optimized kernel. For context, the H100 and A100 matmuls used in Mamba2 get 85-96% compute utilization. Since neither compute nor memory has good utilization in the SSD kernel, the bottlenecks are more complicated than just memory bandwidth or compute throughput.

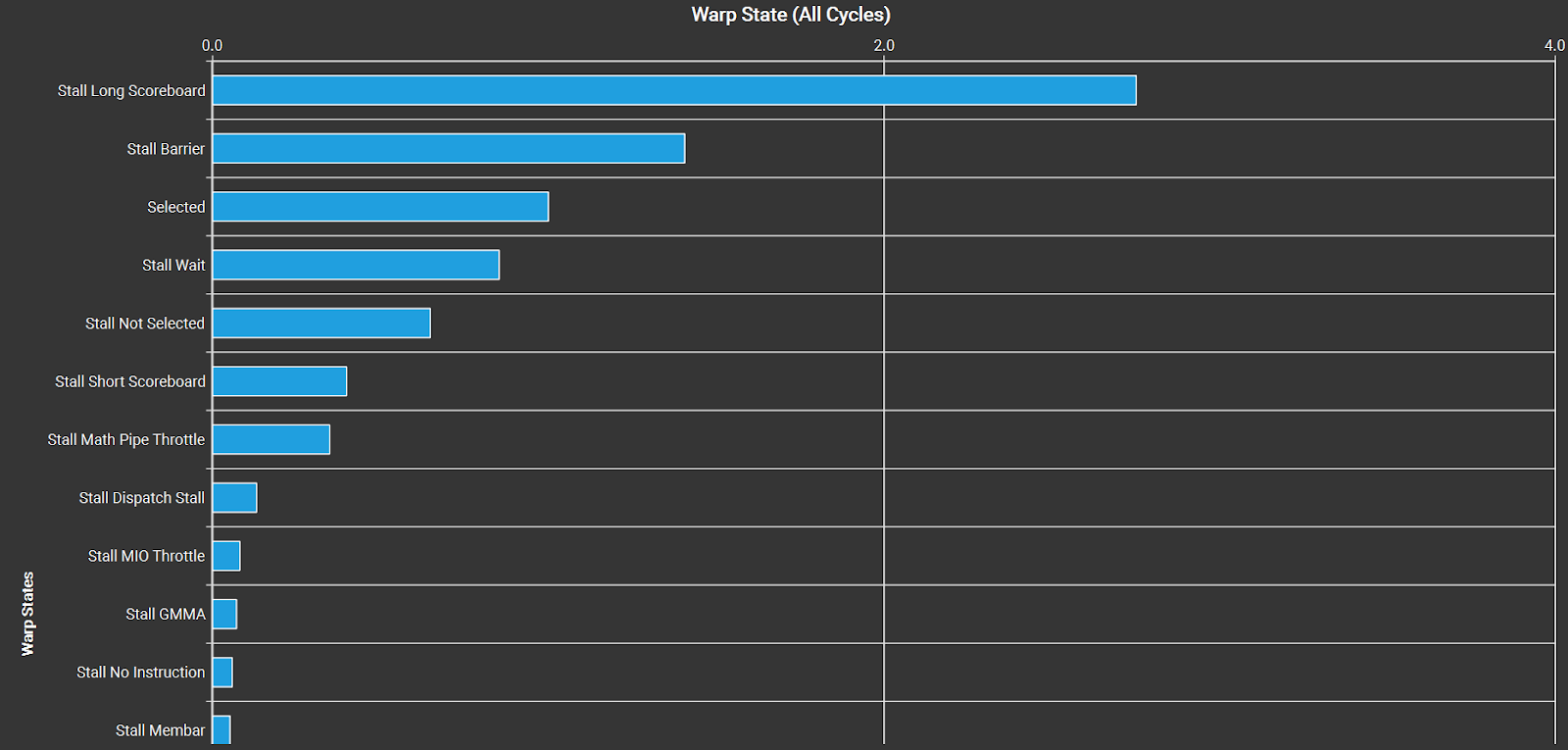

We can look at the warp state statistics to see what warps are stalled on. “Selected” means that the warp executed a new instruction, but “Stall Long Scoreboard” and “Stall Barrier” indicate that warps are idle waiting for L2/VRAM or synchronizing.

Figure 6. Warp State Statistics for the fused SSD kernel on an H100

There are a few ways to reduce the effect of these stalls and improve the compute or memory utilization:

- Increase occupancy

- Increase instruction-level parallelism

- Optimize the code to use less synchronization and memory ops or cache data better

Occupancy

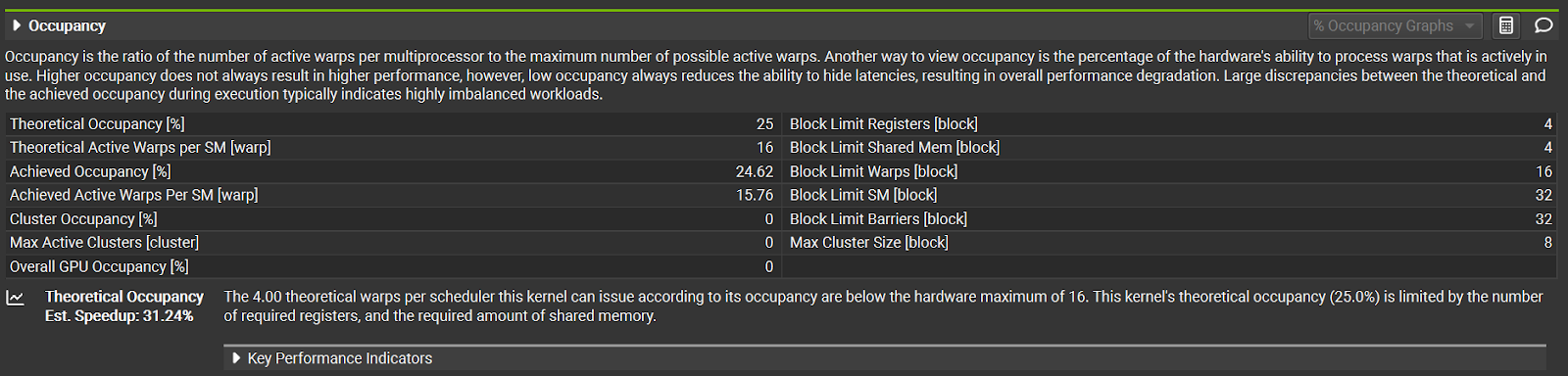

Modern NVIDIA GPUs have 12-16 warps (groups of 32 threads) per warp scheduler, and each of these warp schedulers can issue a new instruction every cycle. If we only have 1 warp in each scheduler, we waste cycles every time that the warp stalls. However, if we have 16 warps in each scheduler, each warp could be stalled about 15/16 of the time without leaving the hardware idle. Occupancy is the fraction of available warp slots that are actually filled with active warps. Increasing occupancy helps hide memory and instruction latency, increasing GPU utilization.

Figure 7. Occupancy for the fused SSD kernel on an H100

This fused kernel only gets 25% occupancy in the current config, limited by registers and shared memory. Although we can increase the number of warps and reduce the registers per thread to increase occupancy, this reduces performance in practice, likely due to increased synchronization costs and higher register pressure.

Instruction-Level Parallelism

Instruction-Level Parallelism means designing/optimizing the code to have less immediate dependencies between instructions, allowing the warp to run future instructions even when the previous instructions haven’t finished. This provides the same latency-hiding benefit as increased occupancy, but without requiring more warps.

Reducing Synchronization and Data Transfer

Since the warps are usually waiting on loading/storing memory or a barrier, we can improve performance by reducing the amount of barriers or reducing total data transfer through better caching or different block sizes.

Unfortunately, these three optimization techniques can directly clash and introduce tradeoffs. Each SM in the GPU has limited registers and shared memory, so if each threadblock uses too much, occupancy drops. We can increase instruction-level parallelism by loading data in stages, but that requires more registers and shared memory, resulting in lower occupancy. We can also change block sizes to reduce the total data transferred or increase the cache hit rates, but this also requires more resources and reduces occupancy.

This is why the fused kernel does not have very high memory or compute utilization.

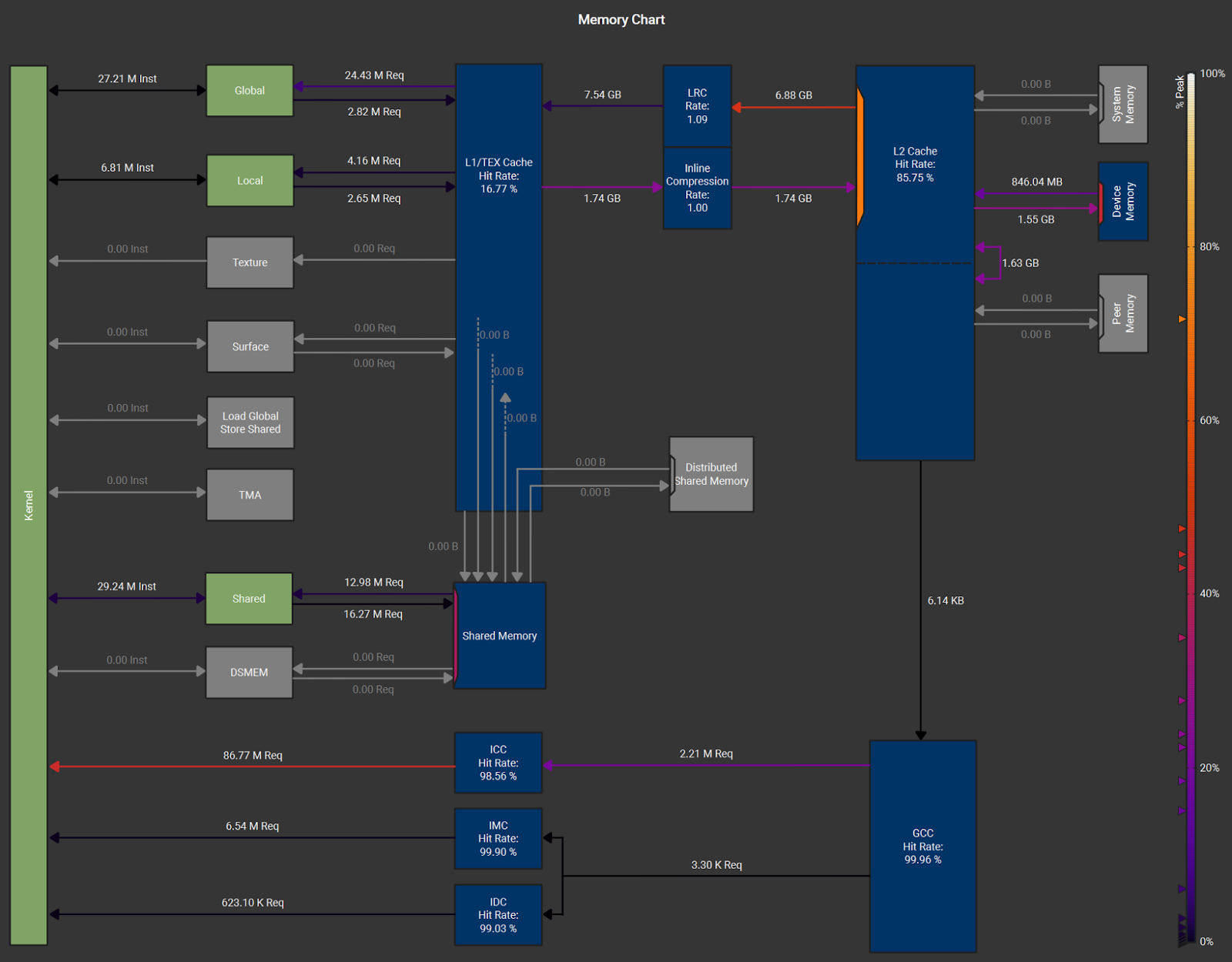

Memory Utilization Details

Figure 8. Memory Chart for the fused SSD kernel on an H100

We can see from this chart that the reported 65–75% memory utilization is mostly from reads through the L2 cache. These reads likely include (i) tensors that fit in L2, (ii) tensors reused across multiple threadblocks, (iii) state transfers between threadblocks, and (iv) VRAM reads that naturally pass through L2. Since L1 caches are private to each SM and not coherent across threadblocks, shifting this traffic to L1 is not feasible. Similarly, bypassing L2 for VRAM traffic would not help, as all global memory accesses pass through L2.

This memory chart suggests that, apart from the suboptimal memory utilization, the kernel is effectively L2-bound rather than DRAM-bound. Further optimization would therefore require either (1) increasing memory utilization, (2) tuning the block sizes / config, or (3) making radical algorithmic changes.

Line-by-Line Stalls

Nsight Compute profiling shows warp stalls line-by-line, helping us check that the warp stalls are for legitimate reasons. As expected, most warp stalls in the fused kernel are from loading data, synchronization, and computation, with only minor overheads from atomics and inter-chunk synchronization. See Appendix B for more details.

Benchmarks

We benchmarked our Triton kernel on typical inference scenarios, batch size 1-32, sequence lengths from 1K up to 256K tokens, and fp16 states. These graphs highlight the speedup of our kernel over the baseline unfused kernels.

Figure 9. NVIDIA A100 Fused Kernel Speedup Graph

Figure 10. NVIDIA H100 Fused Kernel Speedup Graph

The fused SSD kernel is 1.50x-2.51x faster than the unfused implementation on the SSD portion. At low sequence lengths (especially with batch=1), overheads from kernel launches help the fused kernel, but these constant costs become amortized for longer sequences. At higher sequences, the fused kernel’s lower data movement is even more beneficial as cache thrashing increases. The SSD speedup translates to roughly a 8-13% end-to-end speedup for a model like Mamba-2 2.7B with batch=1 and seq=128K on NVIDIA A100 and H100 GPUs. At shorter sequence lengths, the end-to-end speedup can reach ~20% at 1K context, likely due to the reduced kernel launch overhead.

Accuracy and Correctness

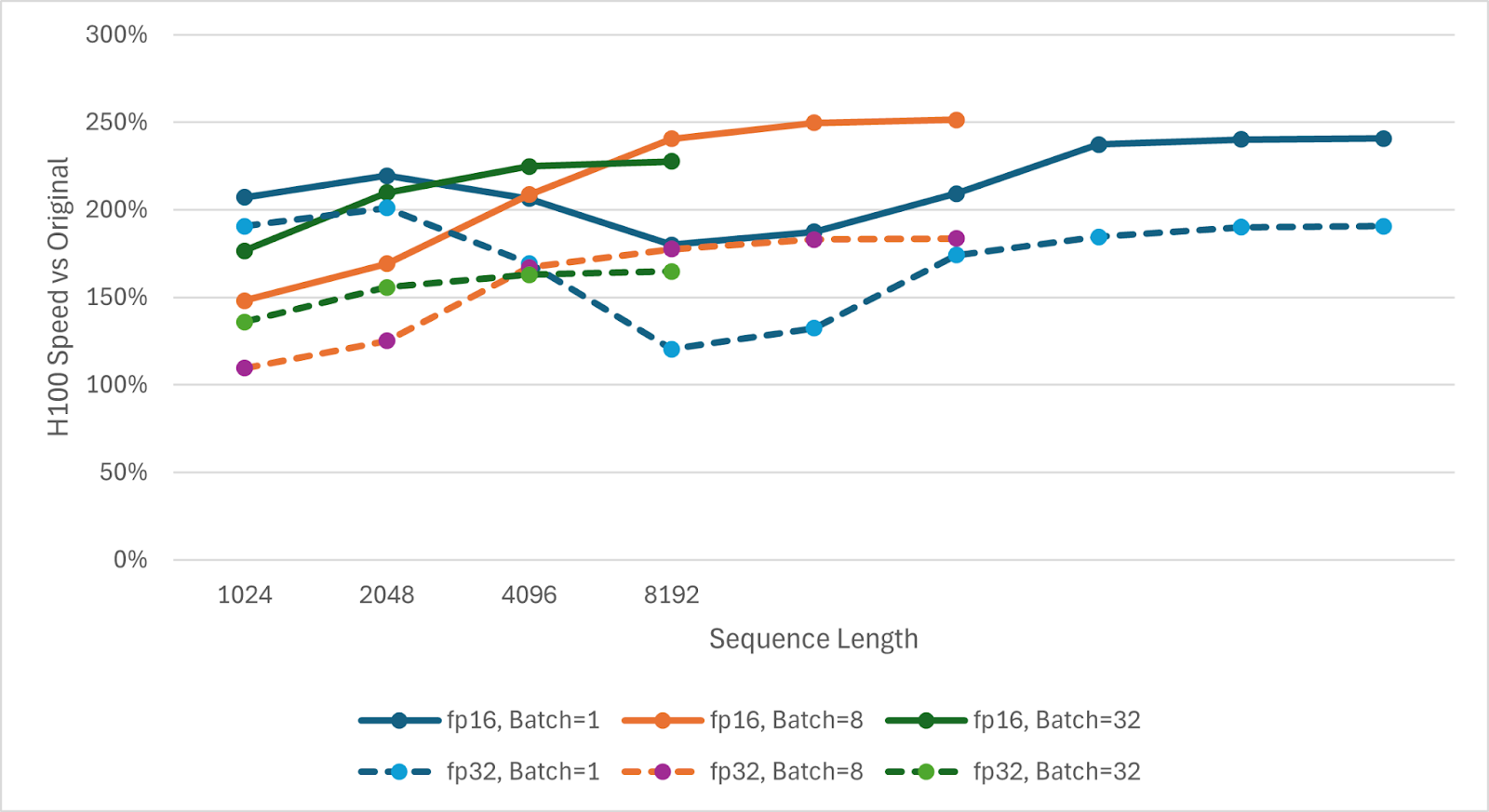

The fused kernel is generally accurate and correct, but there are slight differences in output between the fused kernel and reference solution. These differences depend on the GPU it’s running on and the precisions of some computations. The fused kernel internally uses fp16 for some computations that the original kernels used fp32 for, because this gives a ~16% speedup. Furthermore, the original kernels support either fp32 or fp16 states, but our reported speedups are for fp16 states. The fused kernel still supports the same intermediate datatypes and fp32 states. In this section we explain the tradeoffs in accuracy and performance for these different dtype configs.

In Table 2, we report the accuracy of the output y tensor as percentage of elements that match the original kernels’ output. We test with no threshold (element must exactly match), a small threshold of 1e-3 absolute and relative tolerance, and a medium threshold of 1e-2. In this table, “exact dtypes” refers to using the same dtypes as the original kernel for all calculations, while “relaxed dtypes” refers to using fp16 for a few calculations. Both the fused and original kernels were run with the same state dtype in each column.

| fp32 states

exact dtypes |

fp16 states

exact dtypes |

fp32 states

relaxed dtypes |

fp16 states

relaxed dtypes |

|

| Match @ atol,rtol=0 | 99.696% | 99.337% | 67.307% | 66.823% |

| Match @ atol,rtol=1e-3 | 100.000% | 100.000% | 99.819% | 99.743% |

| Match @ atol,rtol=1e-2 | 100.000% | 100.000% | 100.000% | 100.000% |

Table 2. H100 Accuracy Table

Floating point addition is not perfectly associative, so we cannot expect all elements of the output tensor to match with 0 threshold. Even a different Triton launch config can cause very small differences in outputs from the same kernel. For “exact dtypes” (both fp16 and fp32 states), the output is identical for all practical purposes, so this kernel should work with “exact dtypes” even in the most accuracy-sensitive models. For “relaxed dtypes” (which we use in our speedup graphs), we can see that around 1/3 of the elements do not perfectly match the output of the original kernel. However, over 99.7% of the output elements match if we allow the tight threshold of 1e-3. Furthermore, at the commonly-used tolerance of atol=1e-2, rtol=1e-2 (1%), all configurations achieve >99.9995% accuracy, effectively 100%. For practical purposes, we expect the “relaxed dtypes” to have indistinguishable accuracy.

Figure 11. H100 fp32 vs fp16 Accuracy Graph

In Figure 11, we show how our speedup changes when states are in fp32 instead of fp16. Both the fused and original kernels are faster with chunk_size=256 when states are in fp32. This represents a tradeoff of higher compute in return for a smaller state tensor. The fused kernel’s speedup is less for fp32 states than fp16 states, likely because of the different balance of compute and data movement.

Other Architectures

The fused SSD kernel is not limited to Mamba-2. It also applies directly to linear attention, since the SSD formula reduces to the linear attention update when A = 1. In this special case, the fused kernel could be further simplified and optimized for even better performance.

New GPU Features

The fused SSD kernel does not currently use newer GPU features such as the Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA) and thread block clusters on Hopper GPUs, or the Tensor Memory in Blackwell GPUs. These features can greatly reduce register pressure, which would speed up the SSD and could result in faster Triton configs being possible (e.g., larger block sizes). The thread block clusters could especially be useful for broadcast-loading C, B, and CB matrices that are shared across a group of heads in the SSD kernel. This could give further speedups on new GPUs if necessary.

Further Fusion: Convolution and Layernorm

In this fused SSD kernel, we fused the 5 original SSD kernels. However, the convolution before the SSD and layernorm after the SSD are appealing candidates for fusion because fusing each would remove an entire read and write between kernels. Since the convolution is depth-wise (no channel mixing), the SSD could load d_conv extra along the seqlen dimension and load the conv weights to perform the convolution in registers or shared memory.

We have done some experiments with fusing the layernorm, but with limited benefit. There are two methods to fuse this layernorm:

- Launch layernorm threadblocks separately. These threadblocks can wait until the corresponding SSD threadblocks have finished and then read the output y from L2 cache instead of VRAM.

- Sync SSD threadblocks across heads, exchange norm values, and compute the layernorm in registers or shared memory.

Method 2 was very slow because the SSD threadblocks stalled while syncing and had no other work to do while waiting. Method 1 worked, but reading from L2 instead of VRAM doesn’t provide as much benefit as registers/shared memory. So far, the speedup has been far below the theoretical limit, and it’s unclear whether further optimizations would make it worthwhile given the added complexity.

Insights on Model Design

With the optimized fusion of the five SSD kernels, Mamba2 prefill is now even cheaper than before. This shifts the runtime-accuracy tradeoff for Mamba2 layers, which could make scaling up both the size and the number of Mamba2 layers the optimal balance in new LLMs. More design insights include:

- Compute Intensity: The current fused kernel has low compute utilization at the fastest chunk size, so we might be able to afford slightly more complicated operations. Although we could increase compute intensity by increasing the chunk size, that also increases the required registers and other resources, causing an overall slowdown.

- State Precision: In both the fused and original kernels, the State Passing step must be serial instead of parallel. Although sublinear latency parallel scan algorithms exist, in practice, they can be much slower than the serialized version used in Mamba2. Therefore, minimizing the latency of the State Passing computation as a fraction of the total latency is vital to hiding the serialization latency. If the states can be held in low precisions, such as fp16, this significantly helps the fused kernel. Without a fast State Passing step, we might need to split threadblocks more along other dimensions such as headdim, which would slow down the fused kernel overall.

- VRAM vs L2 tradeoff: Since the fused kernel has higher L2 bandwidth utilization than VRAM bandwidth utilization, the cost of sharing less data across threadblocks is less. If an architecture’s performance benefits greatly from smaller groups, the added VRAM reads could have less of a negative impact on performance than it had with the original kernels. On the other hand, new GPU features such as TMA multicast loads could reduce the L2 bandwidth utilization, speeding up the SSD and reducing this imbalance.

vLLM Integration

In order to support variable length sequences with initial states but without padding, vLLM introduces the idea of “pseudo chunks”. Any chunk with tokens for multiple sequences in it has multiple pseudo chunks, one for each sequence in that chunk. Most of the 5 kernels function the same, with State Passing loading initial states when a new sequence starts. However, Chunk Scan has a larger threadblock grid that goes over pseudo chunks instead of chunks. In order to support this in the fused kernel, we have a for loop to process all pseudo chunks in the current chunk. The vLLM Chunk Scan offset its reads and writes based on where the pseudo chunk starts in the real chunk. We use masking based on the sequence index instead, since masking provides a speedup. Both offsetting and masking read/write the same amount of data at runtime, but the masking might be more predictable for the compiler, better aligned, or just simpler. The vLLM fused kernel is still being integrated, but it shows similar speedup.

Conclusion

In summary, we fused the five Triton kernels of the Mamba-2 SSD prefill into one, yielding a 2x speedup for the SSD itself, which translates into a ~8–20% end-to-end inference speedup. This significantly boosts throughput for models using Mamba-2 layers. We are excited to integrate these kernel improvements into open-source projects so that the community can easily leverage faster inference with Mamba-2 based models. Stay tuned for updates as this fused SSD kernel lands in the Mamba codebase and in inference frameworks like vLLM.

Appendix A: Optimization Details

Threadblock Order

The State Passing step causes serialization. For a given head, all but one threadblock stall waiting for the previous chunk to be ready. When our GPU runs about 256-1024 threadblocks concurrently but only one makes progress, we get a significant slowdown. Some of the serialization is hidden by the latency of the Chunk State step since later chunks could still be computing Chunk State rather than being stalled in State Passing, but this is not enough. We have both the nheads and batch dimensions that represent domain parallelism (independent work) in the SSD. Instead of launching threadblocks for a particular batch and head before moving on to the next, we can launch threadblocks for multiple (batch, head) combinations. If we launch n different (batch, head) combinations for the same chunk before moving on to the next chunk, our serialization drops by a factor of n (instead of only 1 threadblock making progress, n threadblocks make progress). This n must be carefully balanced, because if it’s too large, we lose L2 cache locality for passing states, and if it’s too small, threadblocks stall. As a simple heuristic, we launch threadblocks for all nheads before moving on to the next chunk, but finish all chunks before progressing in the batch dimension. For models with much more or less heads or significantly different dimensions, a more complicated threadblock order could involve explicitly combining nheads and batch and then splitting it into an inner and outer dimension, with the inner dimension launching before the next chunk.

Cache Hints

The input and output tensors of operations such as the Mamba2 SSD are typically too large to fit in cache. For example, the input and output for 16k context in a Mamba2 SSD with 128 heads of 64 dim each in fp16 will each consume 16k * 128 * 64 * 2B = 256 MiB. Typical GPU L2 caches are 40-50 MiB. Therefore, some data will be evicted from the L2 cache during that kernel.

Since most of the output tensor does not fit in the L2 cache, it’s not worth using L2 cache capacity for the output to try to speed up the next operation. We can use a cache hint to indicate that the output tensor has the lowest priority for caches. In general, once we access data for the final time in the kernel, we can mark it as low priority for caches. For often reused data, such as CB (which is shared among heads in a group), we can use a high priority cache hint to reduce the chance of eviction.

We can also avoid flushing L1 cache during some sync atomics by specifying “release” semantics. This tells the compiler that previously written data must be globally visible before the atomic operation (e.g. if we are setting a “ready” flag), but this thread does not need to invalidate any caches.

Conditional Separation

In the State Passing step, we have two special cases: reading the initial state instead of the previous chunk’s global state and writing to the final state instead of to the global states tensor. Although conceptually these special cases should only involve swapping the base pointer to read/write to, the initial and final state conditionals increase register pressure and slow down the fused kernel. To solve this, we can handle the special cases outside of the fused SSD kernel. If we replace the nchunks dimension in our state tensor with nchunks + 1, we can copy the initial states into the 0th chunk and copy out final states from the last chunk. These copies are done using the pytorch sliced assignment syntax, which results in small kernels with negligible runtime or launch overhead.

Intermediate Datatypes

For some computations, such as applying the A decay to B in Chunk Scan, we can use fp16 for the computation instead of fp32. This also swaps upcasting B and downcasting the result with only downcasting the scale, reducing casting instructions.

Compile-Time Masks

Triton requires that the dimensions of blocks of tensors in a threadblock are powers of 2 known at compile time. This forces all stores and loads to operate on power-of-2 blocks that might not divide the target tensor exactly. We therefore use masks to cover the entire tensor but avoid reading or writing out of bounds data (or the next block of data). These masks are the same dimensions as the tensor block. However, these masks are not always necessary because model dimensions like headdim are often divisible by the block size and do not change between different inputs. Triton supports tl.constexpr compile-time parameters and setting them based on other parameters with @triton.heuristics. Therefore, we can automatically enable or disable the headdim dimension of the mask at runtime based on if the headdim is divisible by the block size. Although this occurs at “runtime”, it really only occurs once during the initial JIT compilation of the kernel for this model.

Chunk Size

The Mamba2 SSD algorithm takes asymptotically constant computation per token (computation scales linearly with sequence length), but it has a base case of some chunk size that is computed quadratically. Between chunks, the linear algorithm is used, but within a chunk, the quadratic algorithm is used. For more details, see https://tridao.me/blog/2024/mamba2-part1-model/#state-space-duality.

The optimal chunk size represents a tradeoff of higher computation and resources required vs higher hardware utilization and less intermediate states. With the original unfused kernels, the optimal chunk size for Mamba2-2.7B had been 256. However, with the new fused kernel, the optimal chunk size is now 128 for the same model. This smaller chunk size also has the added benefit of reducing register pressure, making the kernel less sensitive to small changes like enabling masks or using higher precision for intermediate results.

Currently, the convention for Mamba2 models is to specify the chunk size in the model’s config. However, since the optimal chunk size varies depending on the original vs fused kernels, it could be better to use a heuristic or autotune the chunk size. This might not be straightforward since the code surrounding the SSD kernels might assume a particular chunk size.

Scale Multiplication Operand

For Chunk State, we can equivalently apply the A decay to X instead of B, since the dimension to be scaled is the inner dimension of the matmul of X and B. Essentially, we do (X * A[None, :]) @ B instead of (X @ (A[:, None] * B). This is faster, probably due to a more similar layout causing less register data movement. For example, due to the required Tensor Core data layout, each thread might already have the required A values to multiply with its X values, but to scale B, we might have to load in a different layout and shuffle data back to the required Tensor Core layout.

Appendix B: Summary of Stall Reasons

If we look at the source in NVIDIA Nsight Compute, we can see the warp stalls for each line of code and assembly instruction in the fused kernel on an H100. Assuming that the kernel and block sizes are optimal, warp stalls can reveal potential areas for optimization.

- In order to ensure correctness, we use an atomic add to get threadblock ids in increasing order. This accounts for about 3% of the total warp stalls.

- Both the Chunk Cumsum and BMM parts of the fused kernel are very fast, so they only cause less than 2% of warp stalls each.

- Atomically checking that the Chunk Cumsum and BMM threadblocks have prepared data for this Chunk State threadblock accounts for about 1.5% of warp stalls.

- Chunk State has about 12% of total warp stalls in loading dA, X, and especially B. It also has about 7% stalls in barriers related to scaling and using Tensor Cores.

- Despite being serialized along chunks, State Passing has less than 3% stalls on synchronization (including awaiting the previous chunk). Loading the previous states does not cause significant stalling, but updating the state and storing cause about 6% stalls awaiting shared memory or a barrier.

- For the previous state’s contribution in Chunk Scan, loading C is about 5% loading stalls, prev_states is about 3% barrier stalls, and the computation is about 8% barrier, loading (for scale), and instruction dependency stalls.

- The current chunk’s contribution in Chunk Scan has about 13% stalls in loading data and 18% stalls in computation (including scaling).

- The residual (scaled by D) accounts for about 6% of total stalls for loading, shared memory, and computation.

Overall, these stalls are for legitimate reasons and are not easy to optimize away.

Some Matrix Multiplication Engines Are Not As Accurate As We Thought

6 Feb 2026, 10:15 pmWhat is an accumulator in an accelerator’s GEMM engine and why does it matter?

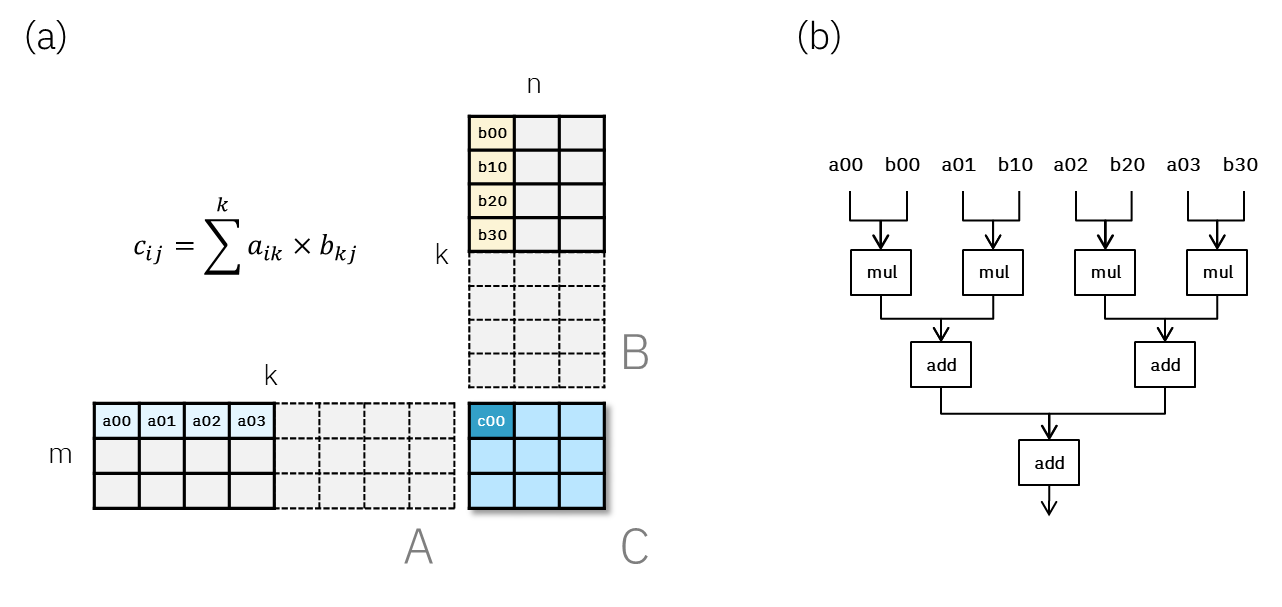

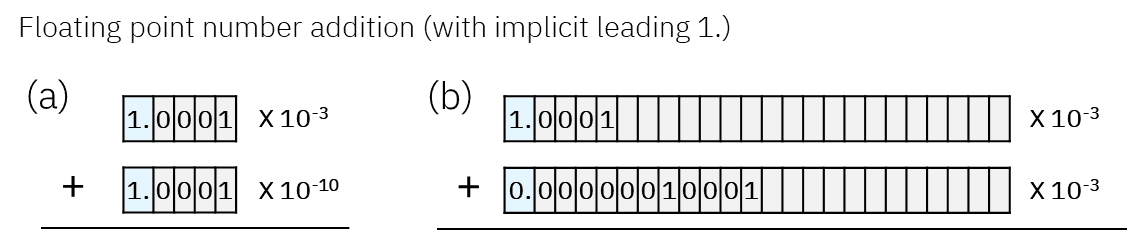

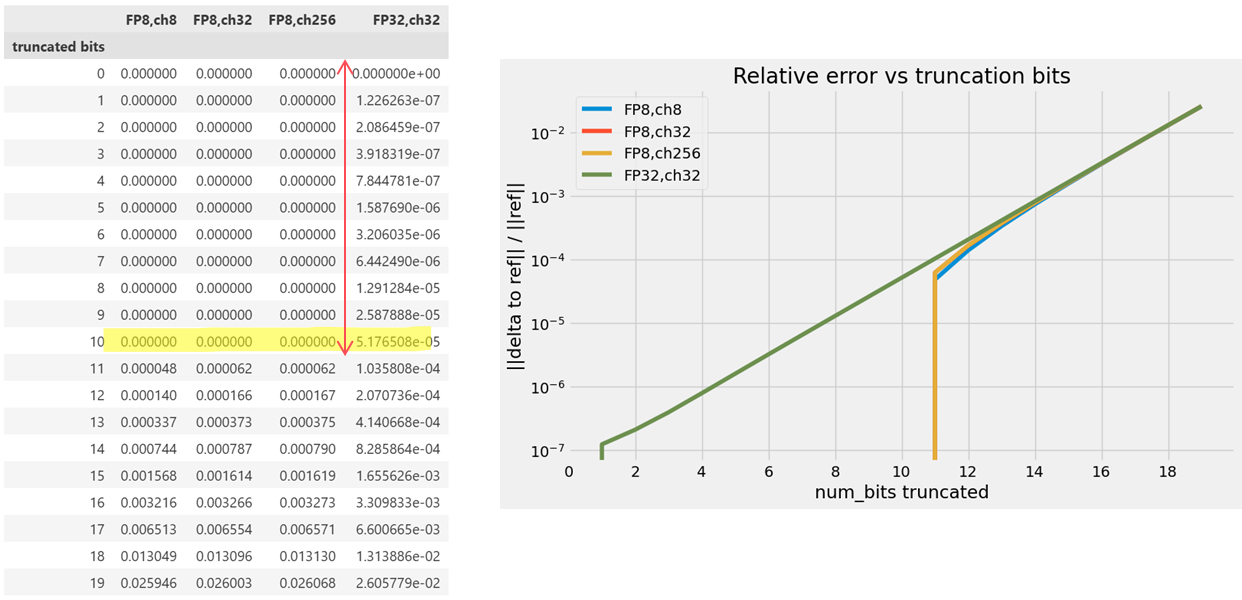

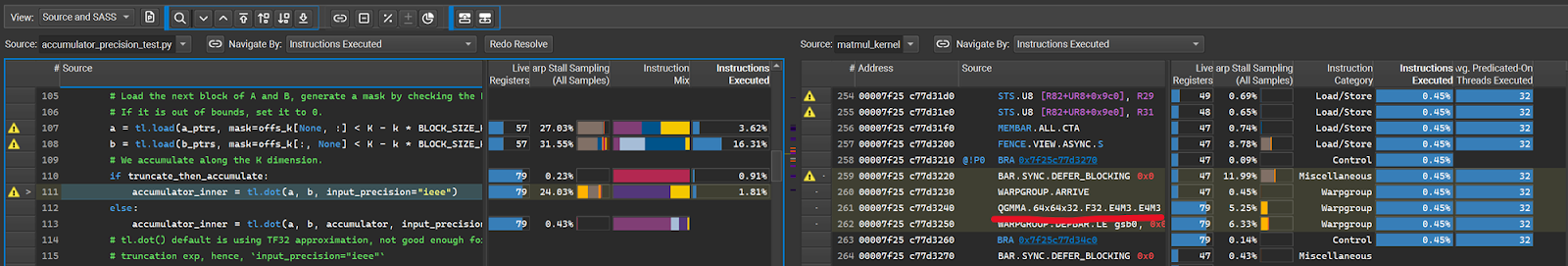

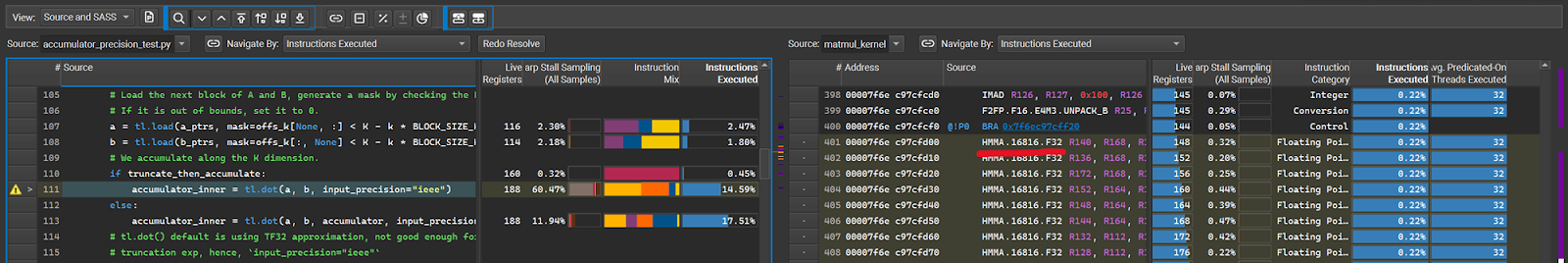

GPUs and custom accelerators include specialized compute engines for matrix multiplication (also known as matmul or GEMM), such as NVIDIA’s Tensor Cores. These engines efficiently perform matmul on small tensor blocks; therefore, compilers or libraries typically divide large matmul problems into many smaller ones and feed them to these engines. Usually, the output from a Tensor Core of FP8 (e4m3) matmul with the shape of (block_size_m, block_size_k) and (block_size_k, block_size_n) is a (block_size_m, block_size_n) tensor in FP32 (e8m23). However, one interesting thing users rarely noticed is that for hardware efficiency reasons, this FP32 output could have fewer than 23 effective mantissa bits. In other words, the precision of this Tensor Core operation is lower than FP32 as it appears. This hardware design choice has been reported to impact model accuracy under certain circumstances 1, 2. Therefore, from a GPU user’s perspective, we would like to verify the hardware design in use. Because even though the existing hardware cannot be changed, custom kernels can still be written in a proper way to preserve highest achievable accuracy when needed. For hardware designers, it is equally important to have a convenient and efficient way to quantify the impact of this design choice.

Before we dive into details, we need to understand the role of an “accumulator” and the reason for employing reduced precision. Let’s first consider a hypothetical compute engine that can handle a FP8 matmul of block sizes (3, 4) and (4, 3), as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Zooming into the compute engine, the most basic operation would be a row-column inner product, i.e.